Limits of Reforms and Conditionalities in Lebanon's 3RF

From 2000 to 2020, the ruling political class endorsed tens of ministerial statements and aid programs that entailed structural reforms. Yet, upon scrutinizing the outcome of these reform pledges, our earlier work demonstrated that the state’s performance was dismal and unachieved promises were recycled.1

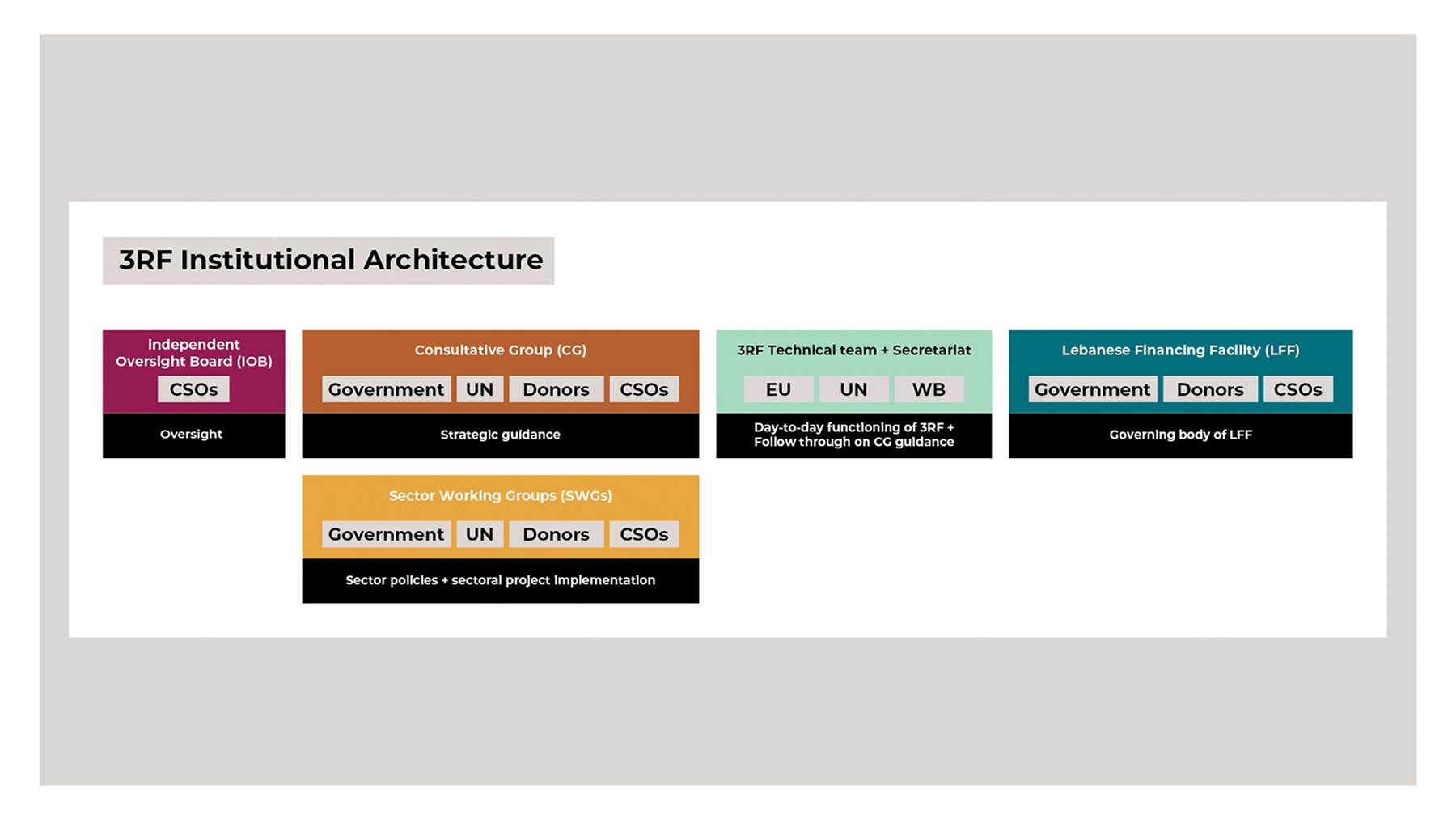

Following the Beirut Port Blast of August 2020, international organizations provided Lebanon with another aid framework, the early phase of which was humanitarian, labeled the Reform, Recovery, and Reconstruction Framework (3RF). Influenced by shifts in aid architecture in other post-disaster contexts, and perhaps mindful of the state’s poor track record, UN agencies, the World Bank, and the European Union built an innovative institutional structure to govern and channel aid that includes Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) in its decision-making structure (Figure 1).2 Moreover, the 3RF conditioned the disbursement of significant concessional financing (about $2 billion) on a list of “critical reforms”, referred to as action points, encompassing 16 sectors including social protection, public procurement, business, and justice.

As this article shows, this new aid architecture largely failed in delivering reforms. Only a fraction of the proposed reforms were implemented and those that require significant political commitment were much less likely to be adopted. Moreover, many 3RF reforms were taken from previous aid programs, which indicates not only the unwillingness of the ruling class to adopt reforms but highlights their strategy to kick the can further down the road. Finally, of the few serious reforms that were passed, all were either delayed, ignored, or voided once they came into law.

Does the 3RF break the trend?

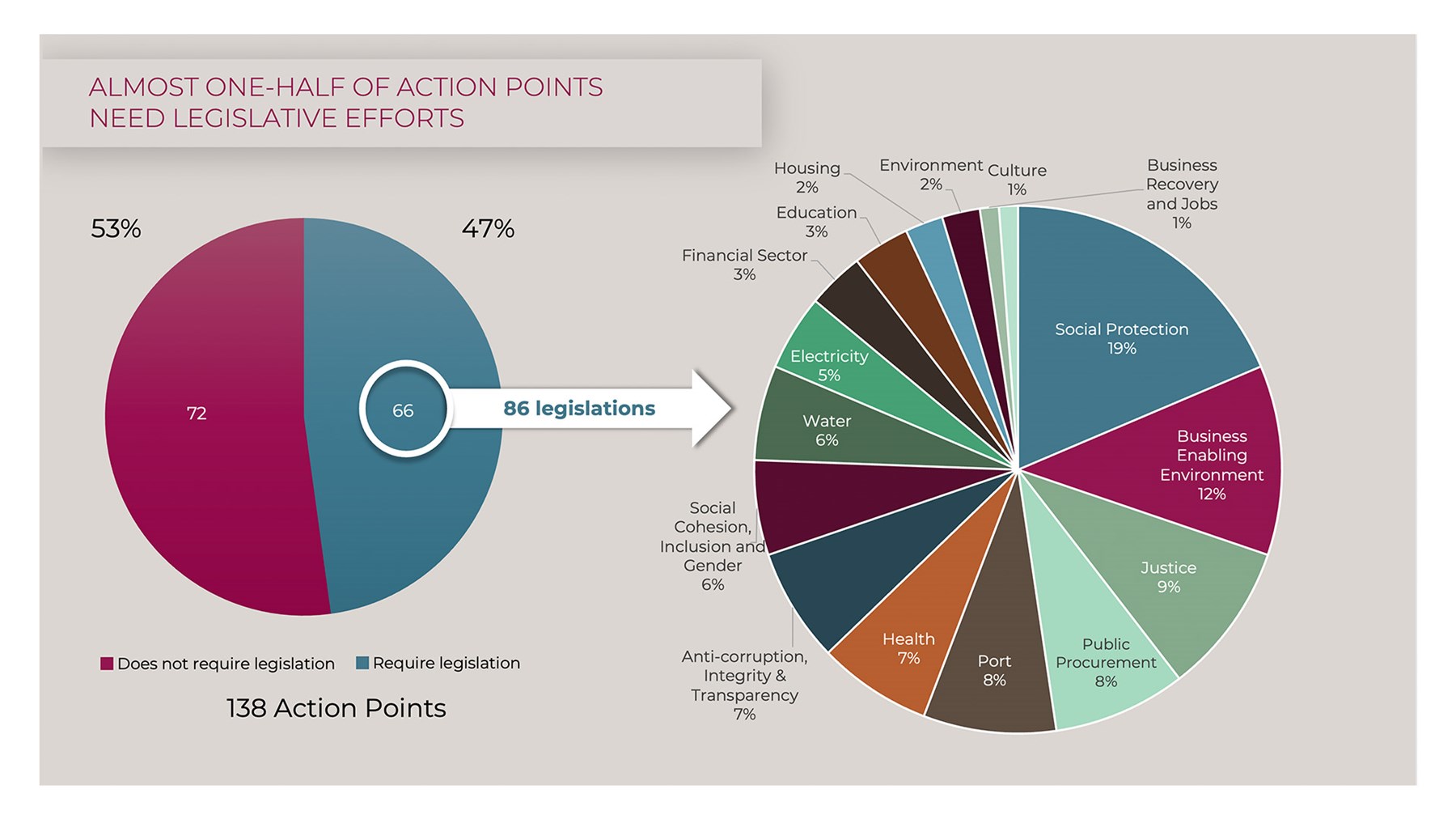

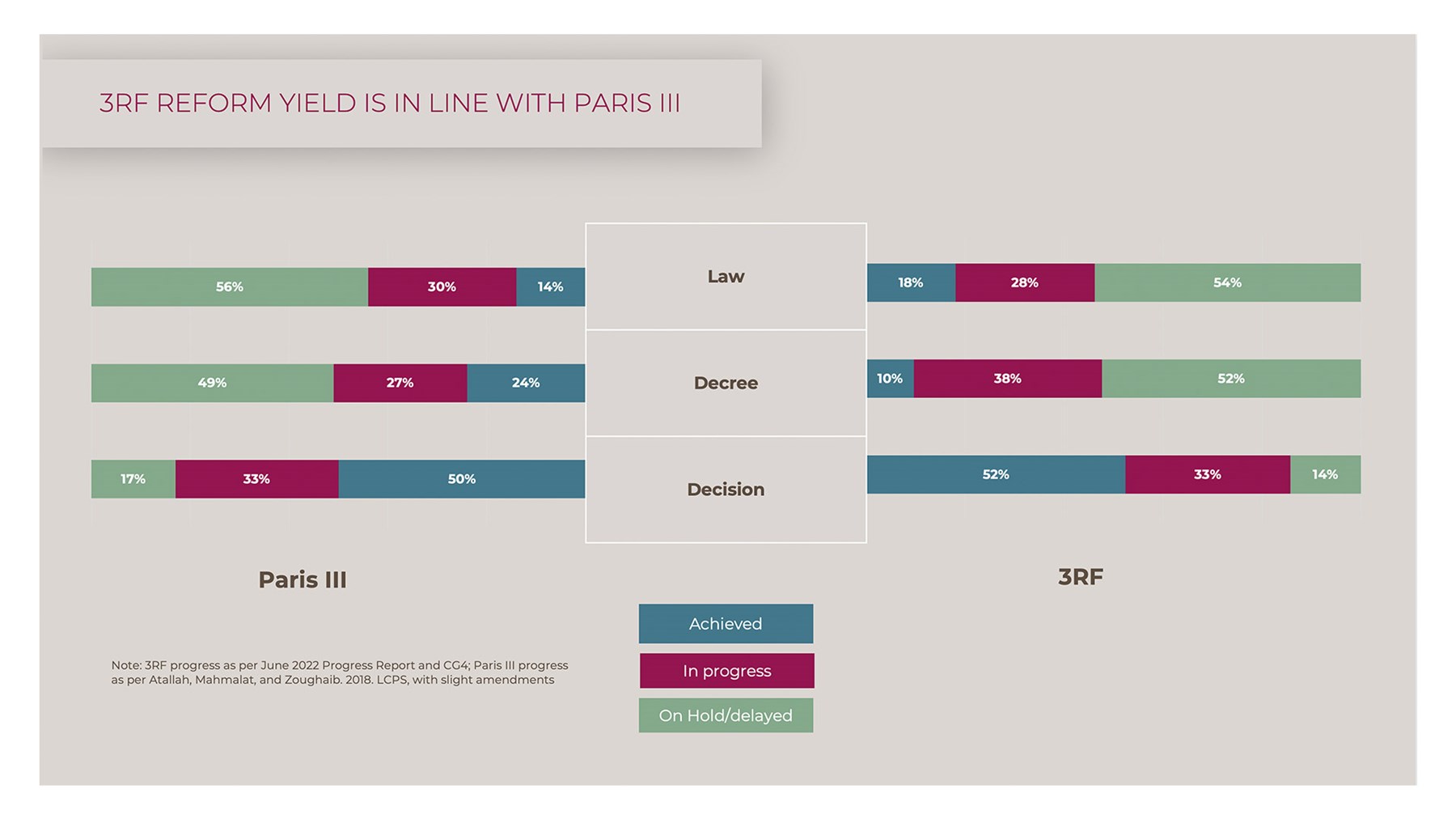

Out of the 138 action points, 66 carry legal implications, which translates into 86 distinct legislative and executive texts that need to be enacted by the Lebanese State. They are predominantly concentrated in the following sectors: social protection, business, justice, public procurement, and port (Figure 2). We unpack these 86 texts further by determining which type of regulatory text they require to be implemented: a law, a decree, or a ministerial decision, each type entailing a different level of political commitment. Laws require the highest level of political commitment since they need consensus among ruling parties, which manifests as a vote in parliament. Ministerial decisions, issued by individual ministers, require the lowest political commitment. Decrees, issued by the Council of Ministers, require moderate political commitment.

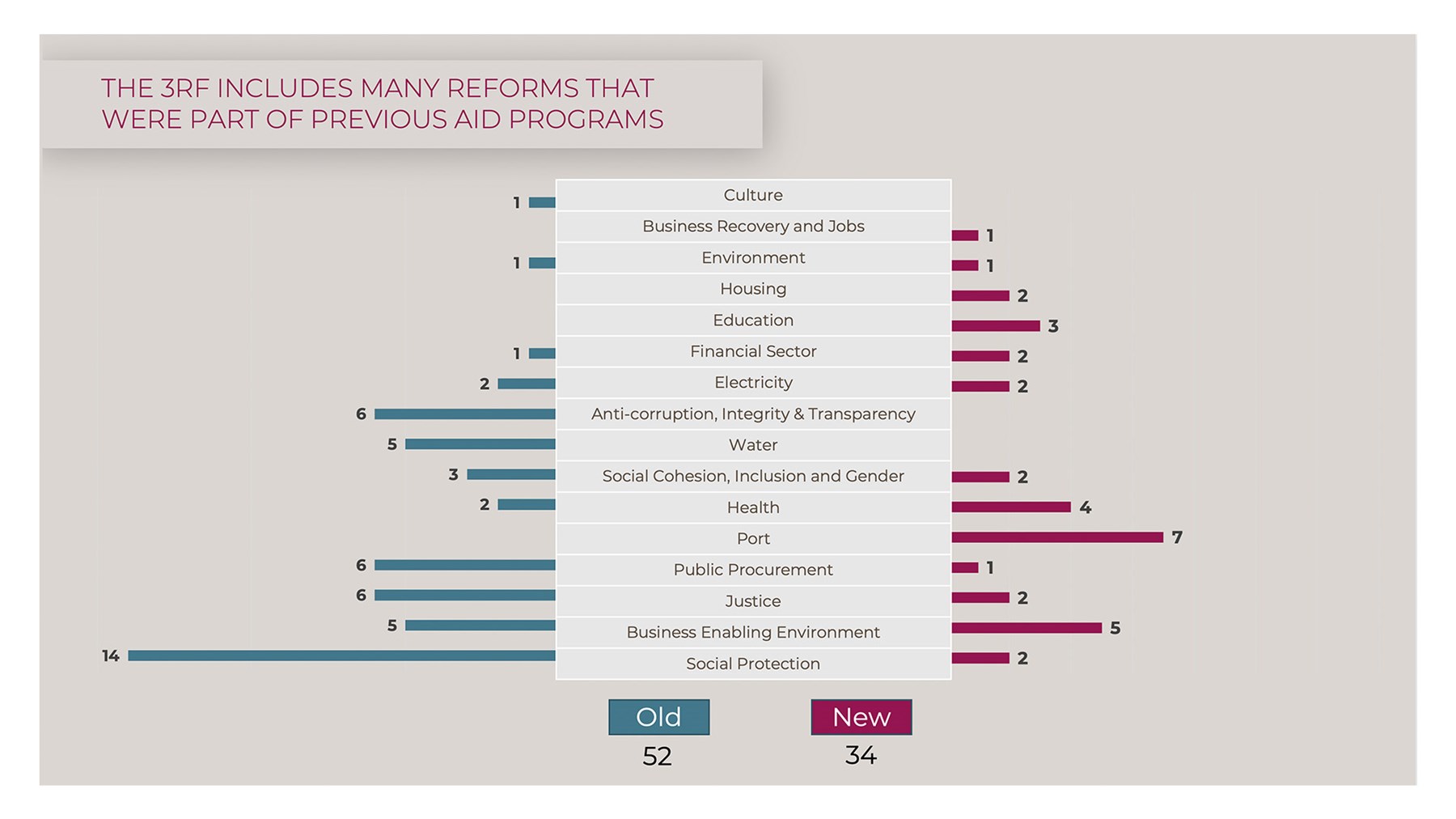

As a new aid framework, 3RF’s reform agenda largely assembles pledges that the Lebanese state made at previous international donor conferences but never achieved. Of the 86 legislative and executive texts outlined in the reform agenda, 52 were previously pledged at Paris III or CEDRE or are part of the government and parliament’s ongoing policy work (Figure 4).

The first concerns the public procurement law, which the parliament passed in 2021 after being pledged at the Paris II conference in 2002. However, the law is not being upheld, as on February 6, 2023, the Council of Ministers awarded a public contract to a firm to conduct cleaning and maintenance work at the Ministry of Education and Higher Education building without issuing an open call for bids.7 More recently, the parliament amended the law to exempt security apparatuses from adhering to it and added conditions that may hamper the competitiveness of a procurement process.

The second example is the expansion of social assistance through the Emergency Social Safety Net (ESSN)—a World Bank-financed social safety program. Ruling political parties passed a law enacting the ESSN in December 2021, though it was signed nearly two years after first being proposed, largely due to multiple attempts to interfere in the program’s design, namely the value of aid to be distributed, the selection process of beneficiaries, and monitoring mechanisms.8

Conditional aid in kleptocratic contexts?

As such, alongside many authors who highlight how the aid industry has become a flawed system prioritizing short-term technical solutions over social and political change (in addition to exacerbating structural inequalities and power imbalances), we are left to ponder the usefulness of conditional international aid programs beyond contributing to self-perpetuating the aid industry itself.9 We are additionally concerned over how, moving forward, the 3RF may be providing rent opportunities to the ruling elite and its networks, given the previous experience of the Council for Development and Reconstruction’s infrastructure procurement contracts secured to their firms, that provides a roadmap they will certainly try to replicate.10

1 See for example Paris III, CEDRE, the Hassan Diab ministerial statement, and the French-endorsed plan: Atallah, S., M. Mahmalat, and S. Zoughaib. 2018. “CEDRE Reform Program: Learning from Paris III.” Lebanese Center for Policy Studies.; Atallah, S., G. Dagher, and M. Mahmalat. 2019. “The CEDRE Reform Program Needs a Credible Action Plan.” Lebanese Center for Policy Studies.; Maktabi, W. and S. Zoughaib. 2020. “The Government Monitor No. 14 – Cabinet’s 100-day pledges: 89% Incomplete.” Lebanese Center for Policy Studies.; Maktabi, W. and S. Zoughaib. 2020. “The Government Monitor No. 16 – The Government Monitor No. 16 – The French-Endorsed Plan: Rebranding Old Reforms.” Lebanese Center for Policy Studies.

2 For more details, check Bloemeke, S. and M. Harb. 2022. “Disaster Governance and Aid Effectiveness: the case of Lebanon’s 3RF.” The Policy Initiative.

3 Atallah, S., M. Mahmalat, and S. Zoughaib. 2018. “CEDRE Reform Program: Learning from Paris III.” Lebanese Center for Policy Studies.; Atallah, S., G. Dagher, and M. Mahmalat. 2019. “The CEDRE Reform Program Needs a Credible Action Plan.” Lebanese Center for Policy Studies.

4 We use the 3RF’s June 2022 Progress Report to track the progress on action points.

5 Atallah, S., M. Mahmalat, and S. Zoughaib. 2018. “CEDRE Conference: The Need for a Strong Reporting Mechanism.” Lebanese Center for Policy Studies.

6 Atallah, S., M. Mahmalat, and S. Zoughaib. 2018. “CEDRE Reform Program: Learning from Paris III.” Lebanese Center for Policy Studies.

7 مجلس الوزراء. شباط 2023. "من محضر جلسة مجلس الوزراء." رقم المحضر35، رقم القرار28. Accessed here: https://twitter.com/ElGherbalOrg/status/1623958019355598848

8 Maktabi, W., S. Zoughaib, and S. Atallah. November 2022. “Near Miss: Lebanon’s ESSN evades elite capture.” The Policy Initiative.

9 See for instance: Easterly W., 2006, The White Man’s Burden: Why the West’s Efforts to Aid the Rest Have Done So Much Ill and so Little Good, Penguin Books; Mosse D., 2005, Cultivating Development: An Ethnography of Aid Policy and Practice, Pluto Press; Polman L., 2011, The Crisis Caravan: What’s Wrong with Humanitarian Aid, Metropolitan Books; and Hickel J., 2017, The Divide: A Brief Guide to Global Inequality and its Solutions, Windmill Books.

10 Mahmalat M., S. Atallah, and W. Maktabi March 2021. “The Value of a Seat at the Table: How Elites Interfere in Lebanon’s Public Infrastructure Procurement,” Lebanese Center for Policy Studies.; Mahmalat, M. and W. Maktabi. September 2022. “Cartels in Infrastructure Procurement – Evidence from Lebanon.” The Policy Initiative.