Syrian-Owned Businesses in the City

After the mass arrival of Syrian refugees to Lebanon, a prevailing perception is that Syrians are establishing businesses and competing with the Lebanese, leading to violent reactions on the part of host communities. This study seeks to debunk the reductionist framing of ‘the Syrian refugee’ as a burden, and showcase the economic contribution that some Syrian entrepreneurs have been making to urban neighbourhoods.

×

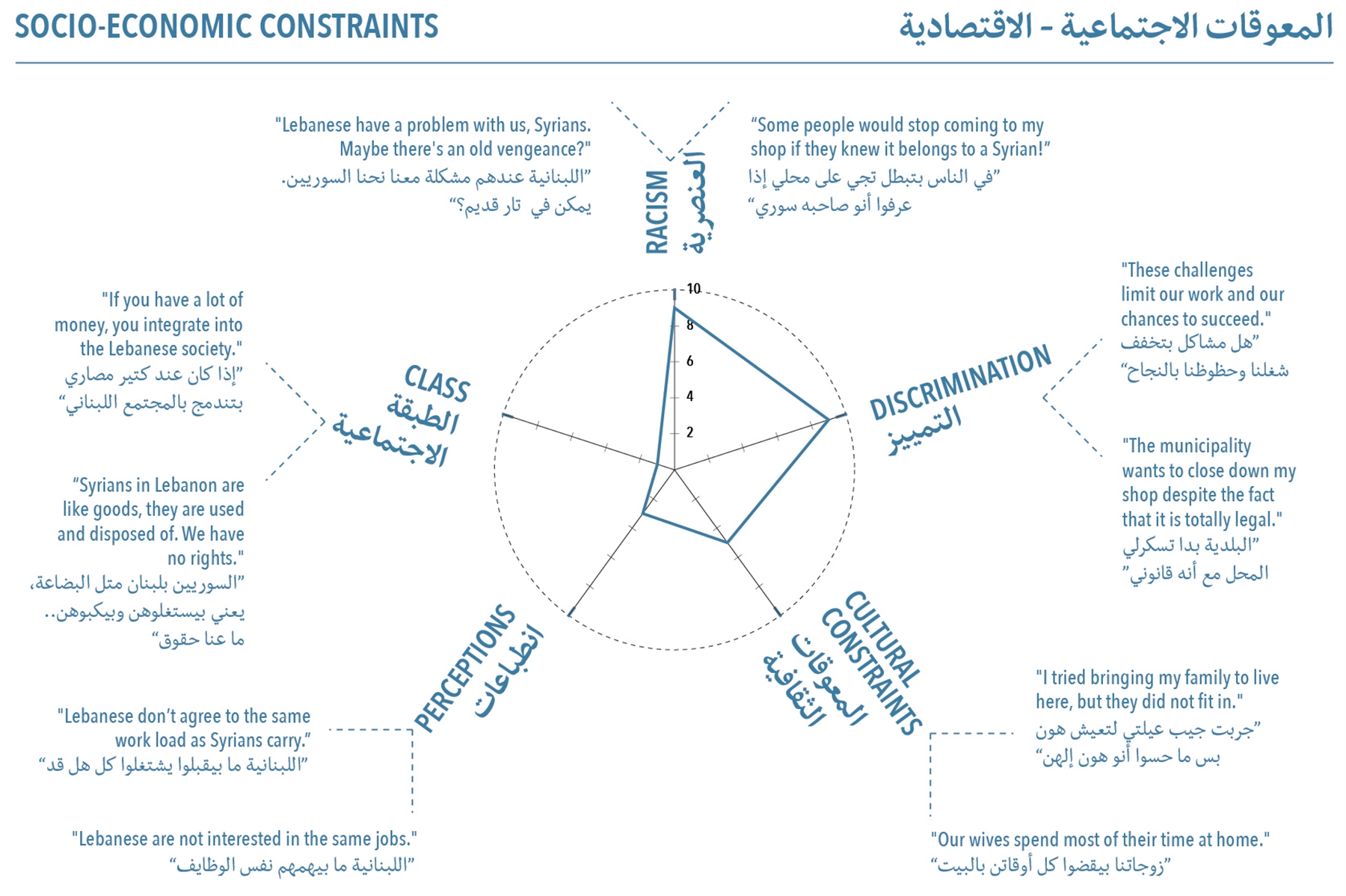

For this study, we conducted in March and April 2017, twelve face-to-face interviews with Syrians who came to Beirut after the war and established small and medium businesses predominantly in Hamra, but also in Tariq el-Jdideh and Aramoun. We conducted semi-structured interviews with them, then extracted from their discourse the concerns that they expressed about their businesses, about their legal status, their mobility, the socio-economic constraints they meet, their relationships with Lebanese business-owners and clients, their relationships with the city itself.

×

While business-owners certainly represent a minority of the refugees in Lebanon, we argue that, rather than being competition, Syrian entrepreneurs are complementary to Lebanese businesses in urban areas, and that Syrian businesses are enriching spatial practices in the city. As such, we claim their experiences are significant to document as they can inform useful policy interventions that can render Syrian self-employment an opportunity for local economic development in cities and towns.

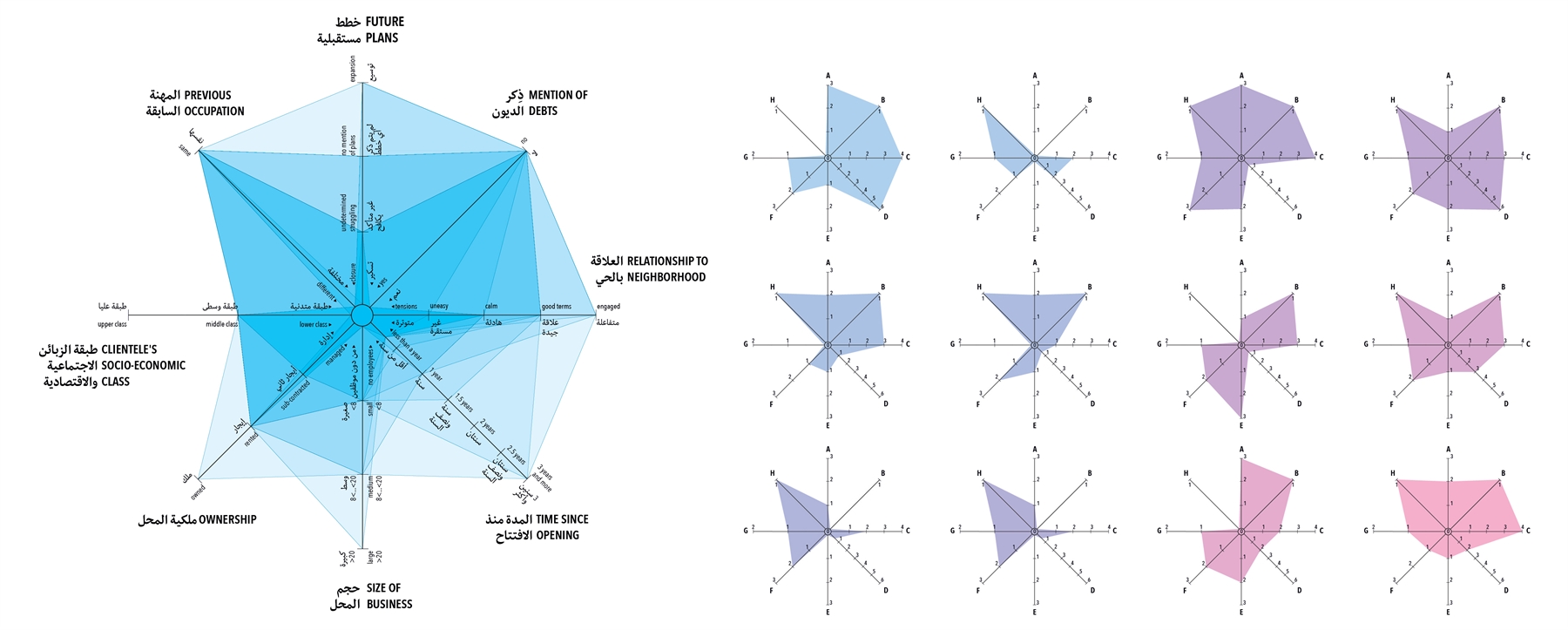

This spider chart shows different characteristics of the twelve profiled businesses. When overlaid, the profiles can be compared across the different measures, distinguishing between common and exceptional attributes. For example, none of the interviewed entrepreneurs’ businesses caters to a high-end clientele, almost all mention carrying debts, and only one of them owns the shop in which the business operates.