Beirut is a dense city with high levels of urbanization, where open public spaces are scant, poorly designed, and ill-managed. The commodification of land has transformed neighborhoods in drastic ways at the expense of public life. Yet, neighborhoods incorporate many vacant properties—built, unbuilt, unbuildable, public, private—that hold valuable opportunities for rethinking public life in the city. How can an engaged urban practice reactivate spatial practices and public life in Beirut’s neighborhoods?

Beirut's municipal territory includes 21 public parks and gardens, a seaside Corniche, and a few publicly accessible coastal sites. The total area of parks and gardens amounts to less than 1 sq.m. per resident. Over the past fifteen years, multiple factors have commodified the city and consecrated the exchange value of land over its social value, transforming urban neighborhoods in drastic ways at the expense of these spatial practices. Yet, the city still retains instances of a rich public life, deeply rooted in its urban history, experienced through its streets and markets, but also through multiple spatial practices that unfold in public and private open spaces, more or less hidden, such as alleys, staircases, building entrances, vacant lots, and other random sites. Some of these sites are also rich with a vegetation that stirs the senses and shapes our affective relationship with the city.We believe spatial practices can, and should be un-archived, recovered, and reclaimed. We also believe that urban planners and designers can play a crucial role in advocating and organizing for their reclamation, in close partnership with city dwellers (and city lovers), urban activists, and concerned public and private stakeholders.

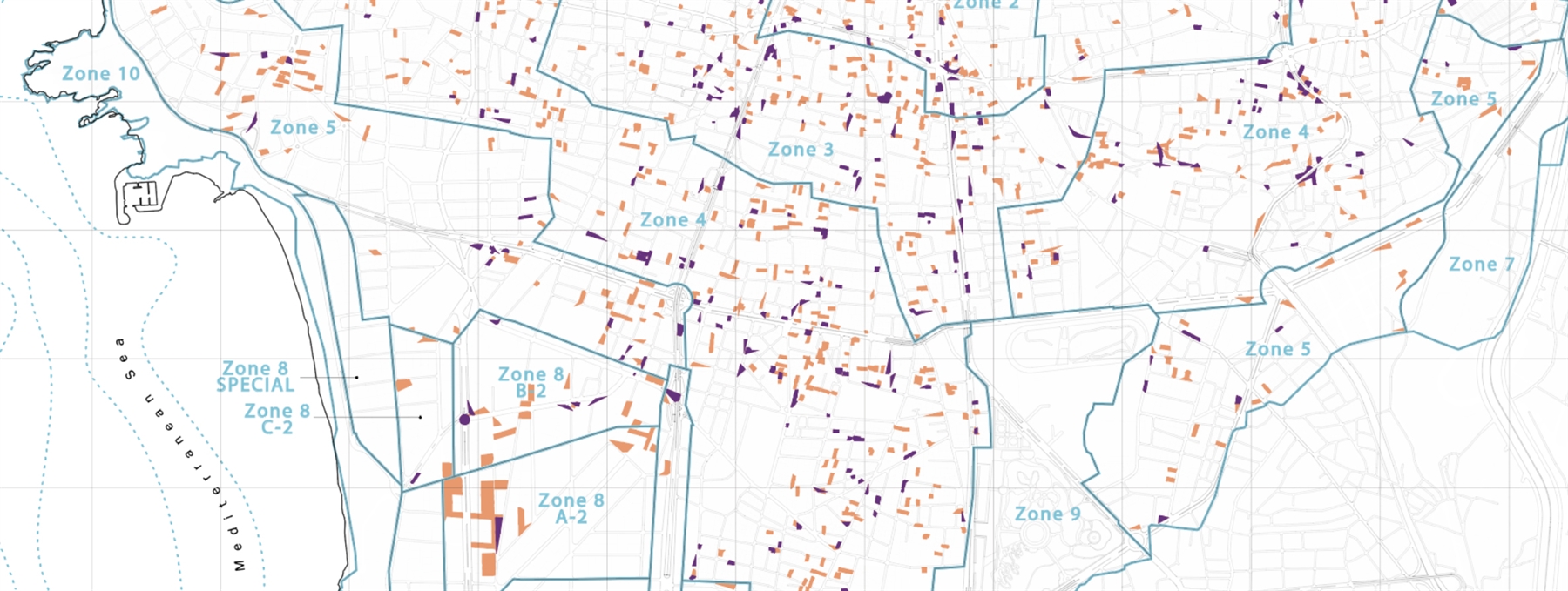

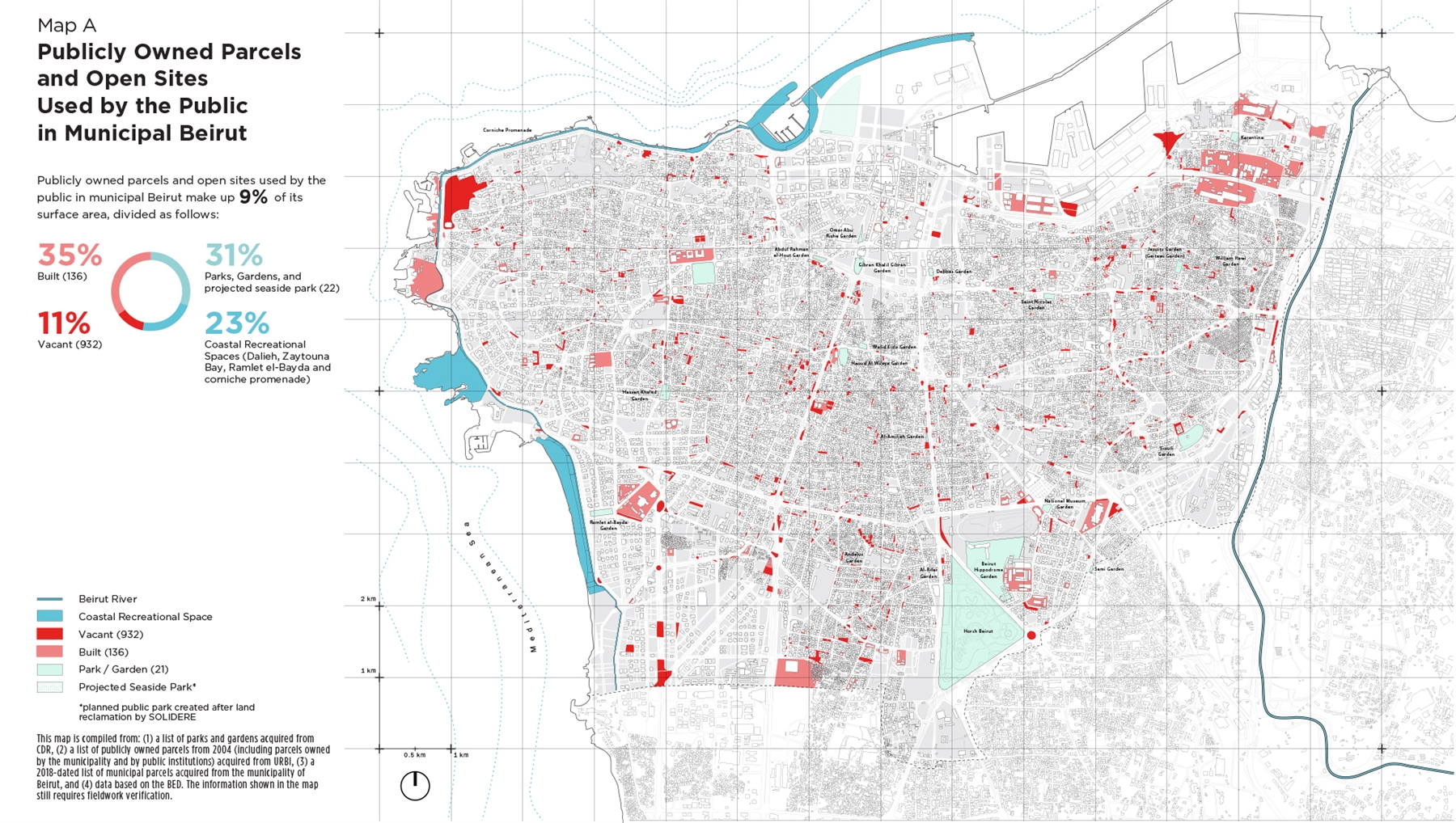

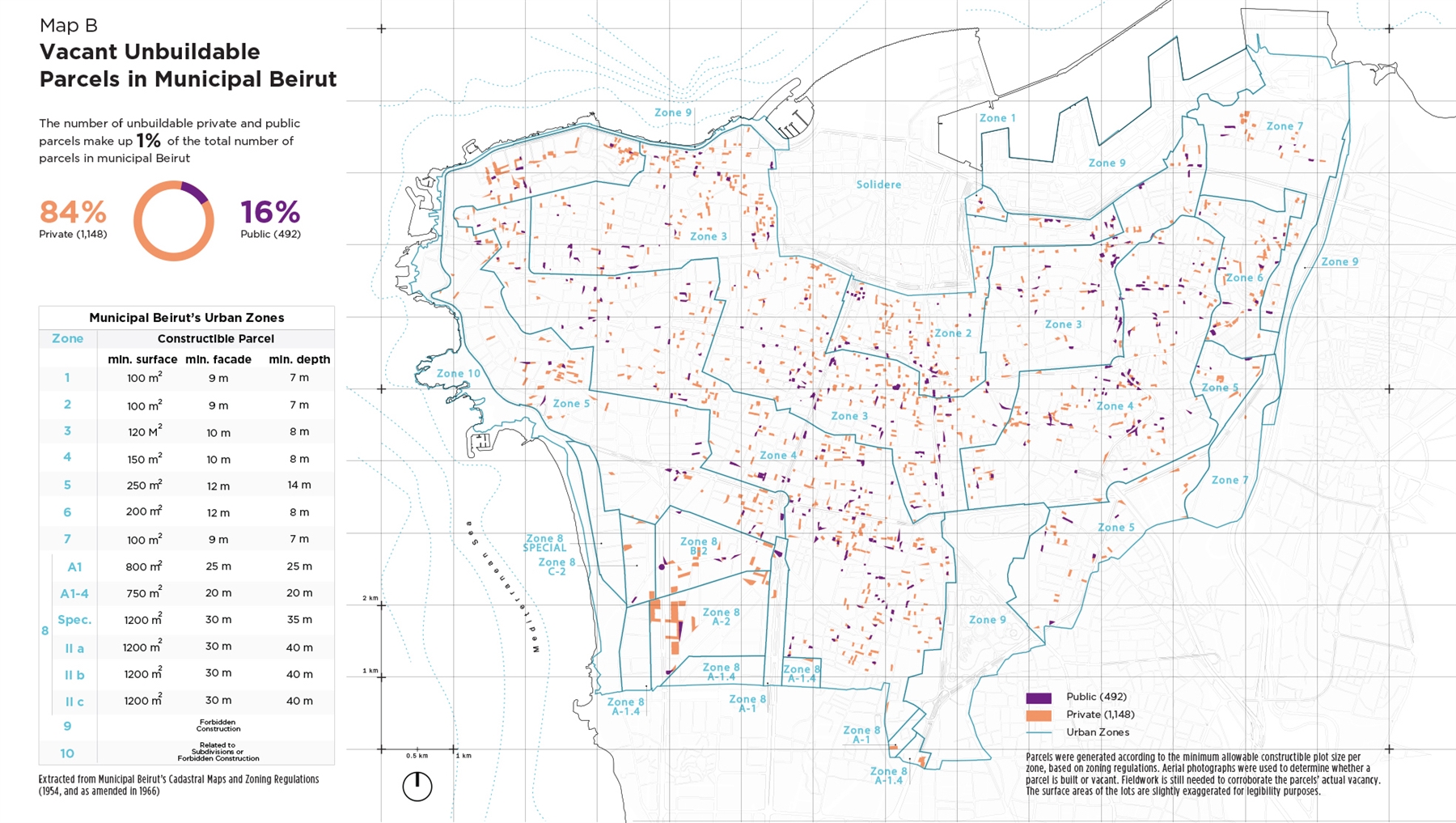

Our mapping of publicly-owned parcels and open sites used by the public (Map A) and of vacant unbuildable parcels (Map B) in municipal Beirut aims to underscore the multiple remaining opportunities that can still be captured to reactivate public life in the city. Indeed, Beirut incorporates many vacancies, built and un-built, public and private—some of which are sometimes appropriated, often for private ends, more rarely for shared uses.

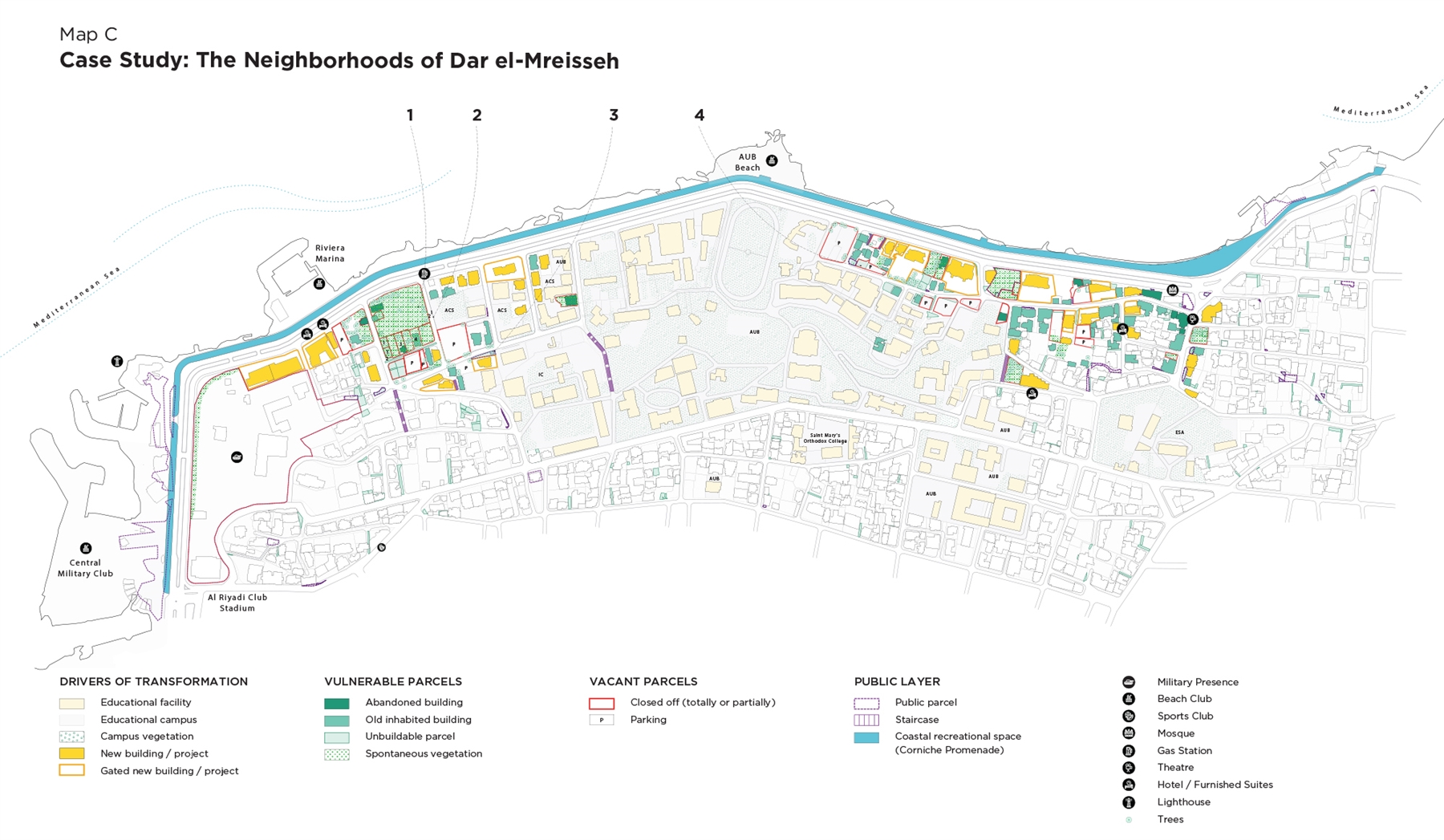

We test further our proposition in Dar el-Mreisseh (Map C), where we undertake a detailed mapping of the drivers of urban transformation in the neighborhoods (namely educational facilities and gated residential buildings), available vulnerable and vacant parcels, including their peculiar wild vegetation, as well as public parcels and staircases. Through this work, we seek to show how, against commodification odds, vacancies in Beirut’s urban fabric provide multiple opportunities that we could capture to help foster a vibrant public life—one inclusive of people, memories, nature, and senses.

Large parcel with a rusted metal fence, overtaken by wild vegetation. Closed off for decades, the parcel was acquired by an Emirati company for building the Sheraton Hotel back in the 1960s. Today, the parcel remains closed off with an abandoned two-storey building on site (Photo: Tala Chehayeb, March 2020)

Linear pocket garden lining the back of the ACS sports building, including a plastic white chair; we were told by the woman living in the adjacent old building that the garden is maintained by her brother (Photo: Myriam Khoury, March 2020)

AUB parking lot used sometimes as break area for AUB janitors (Photo: Ranime Nahle, March 2020)

Aridi-Choucair house built on a 36 m² unbuildable parcel. According to a concierge nearby, before the building was built in the early 1990s, Aridi-Choucair used to own another house, located in the middle of what is now the street. The developers destroyed it to secure street access to the new building, and rebuilt a new smaller house for the Aridi-Choucair in what remained of the parcel (Photo: Myriam Khoury, March 2020)