Mapping Security in Beirut: A Decade of Research

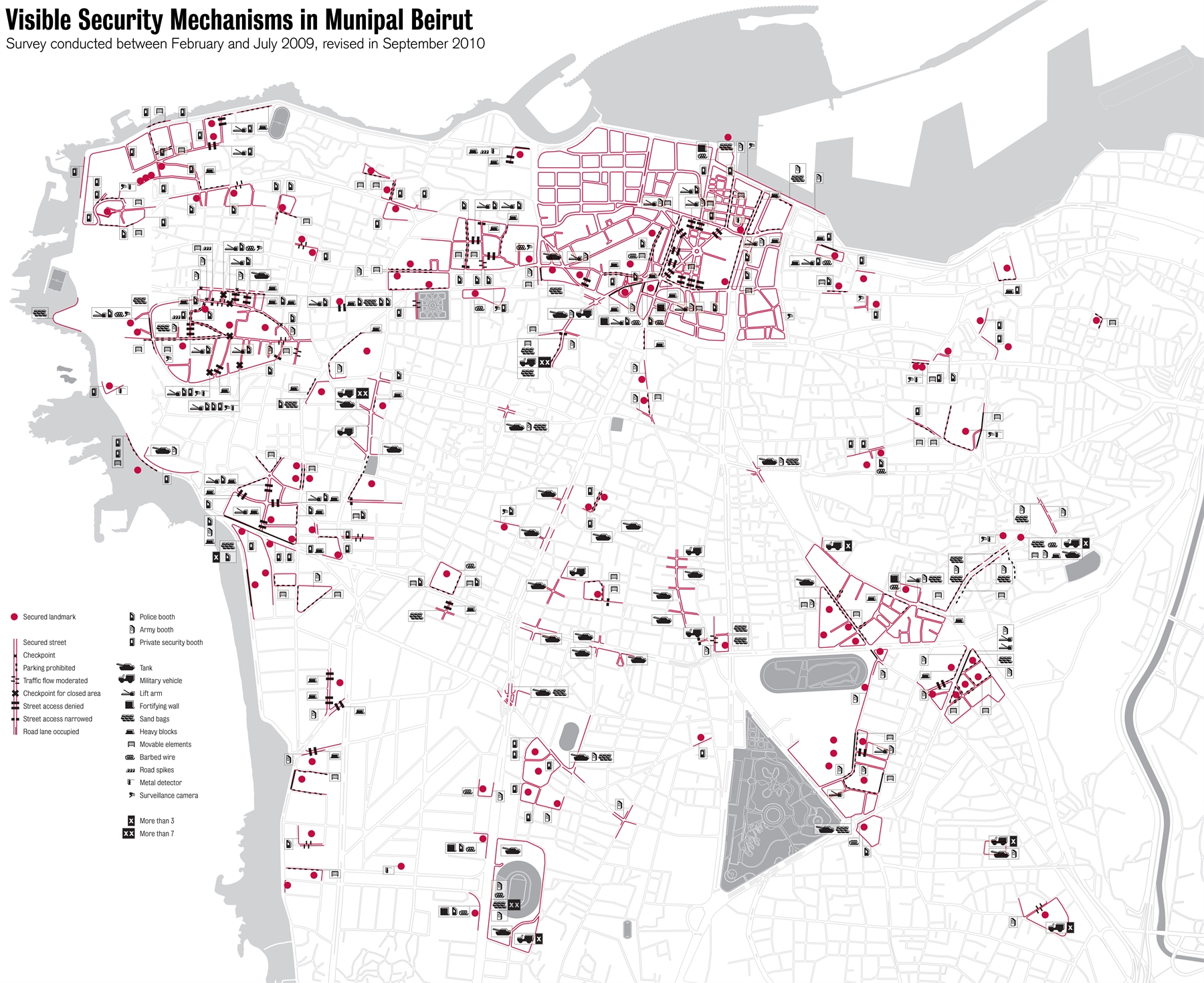

Militarized security is perhaps one of the most defining aspects of Beirut’s public and shared spaces. Not only does it substantially influence everyday life, but it also reorganizes the city’s multiple publics, enforcing numerous forms of restrictions on some of the city’s users, while facilitating the fluid circulation of others. A closer look at Beirut’s militarized security reveals that what reads as a homogenous layer is in reality composed of heavily fragmented units that are managed by overlapping and decentralized systems that often blur the boundaries between public and private realms. Through the years, we have conducted several projects exploring the deployment of security, its effects on the reorganization of the urban geography of the city, and its repercussions on the daily practices of various groups of city users.

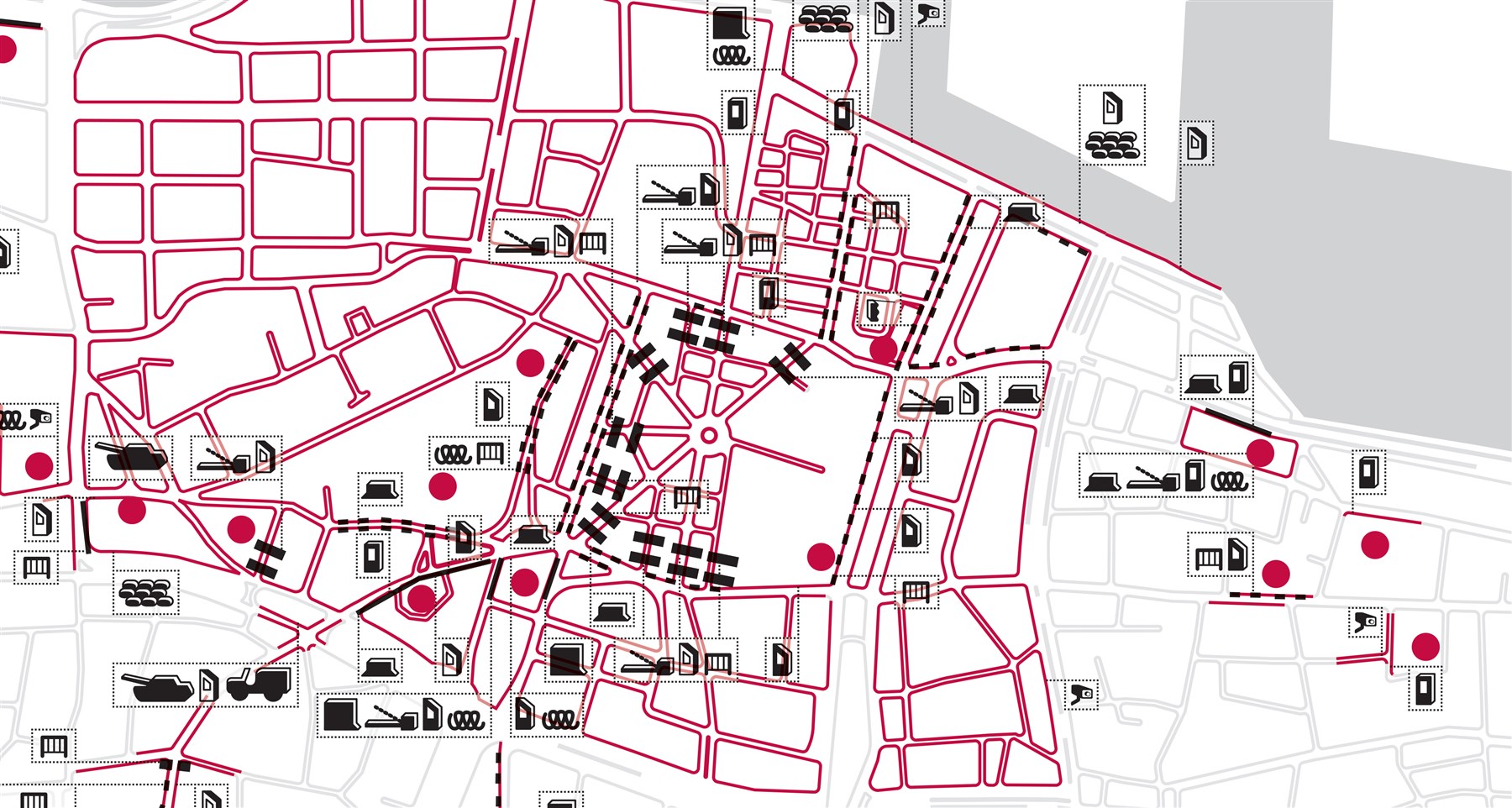

2009: Mapping security mechanisms in Municipal Beirut

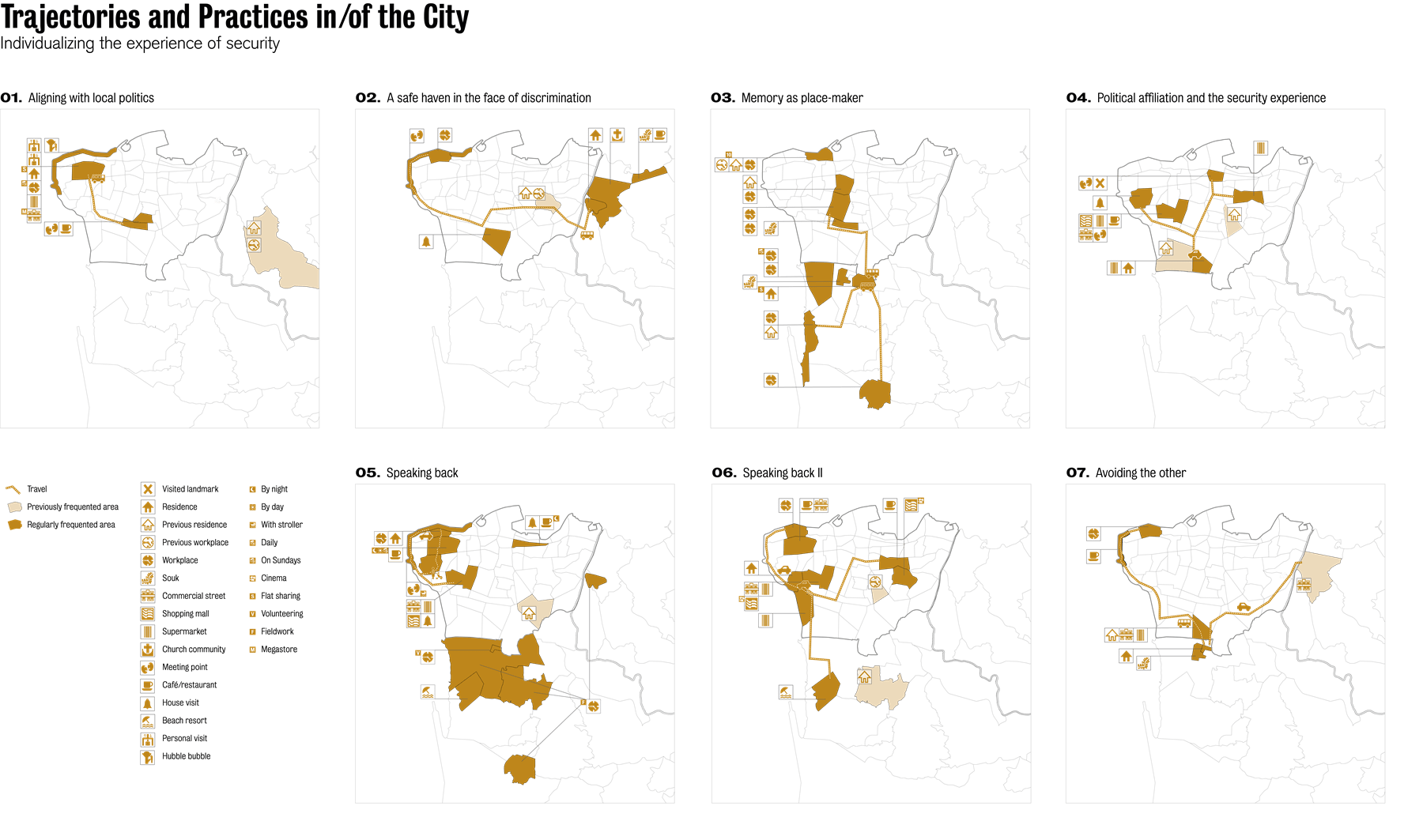

2018: Refugees as navigators of the militarized security of Beirut

In investigating the role of refugees as city-makers, militarized security emerged as a central concern of everyday practices particularly in influencing urban mobility and the visibility it entails. Indeed, an integral element of the refugees’ rising competence in navigating the city rests in learning how to read and circumvent harassment deployed either by the police force or by local strongmen who seek to impose their authority through specific territories. This was imperative as Lebanon’s regulatory framework effectively criminalized the presence and labor of refugees, consequently enhancing their vulnerability to the security apparels. Through the mapping of young Syrian men working as delivery drivers, opening businesses, or rebuilding a sense of home in Beirut, we learned that militarized security was an essential determinant of the choices of everyday mobility and residency. Security determined trajectories. Security also framed “hot spots”, zones completely outside one’s practice, and defined “scheduled access” for areas where deployment intensified at night. Practicing security was also a competence one acquired. Thus, interviewed delivery drivers spoke of “evading” harassment as part of the skill set one learns in their occupation, a knowledge at least as important to navigate the city as the city’s roads and pathways. It involves checkpoint prediction and avoidance, maneuvers to avoid tickets, and modes of circumventing any hurdle that can be bypassed. Aside from competence building, the task requires an infrastructure of information sharing which delivery drivers have secured through social media platform and cellular communication platforms on which they regularly share information about new and/or temporary hurdles –particularly checkpoints. Ultimately, one can speak of a networks of information sharing that connects refugees working as delivery drivers with other refugees in the business, but also, more generally, with trusted groups of motorcycle drivers, irrespective of national or religious belonging, who mutually support each other by warning against checkpoints or other street dangers.