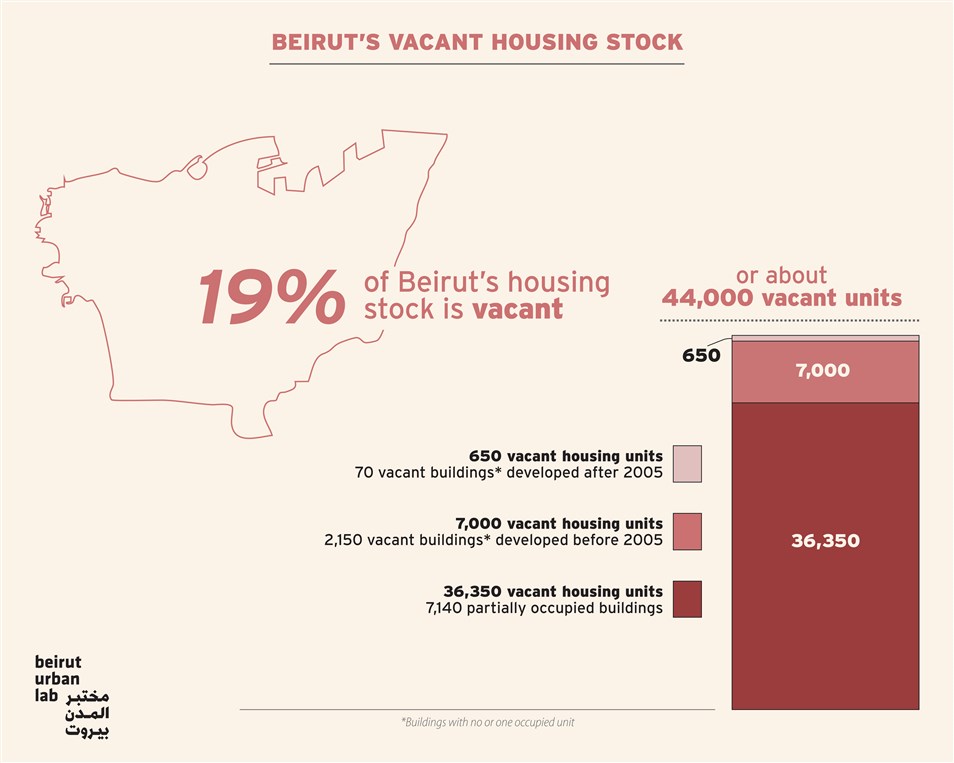

Homeless in the City of the 44 Thousand Empty Homes…

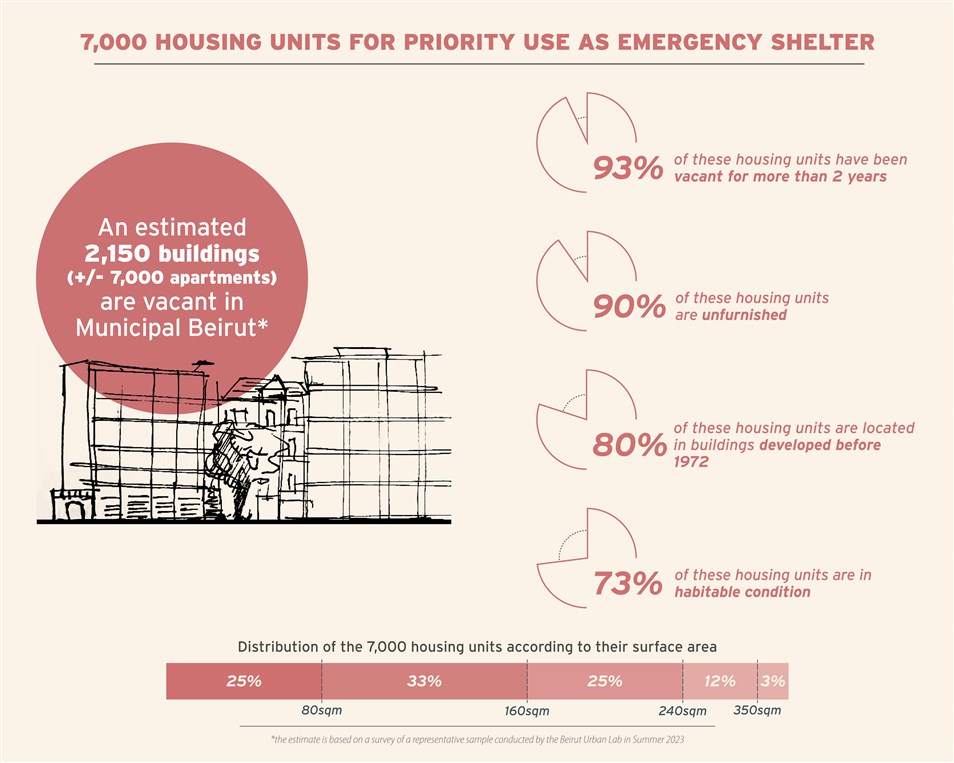

In this short piece, we argue for the urgency of including Beirut’s vacant buildings in a medium-term emergency shelter response for the city. Secured and managed through a public actor and a reliable framework, a section of Beirut’s large stock of vacant apartments should be used as temporary shelters. By activating this building stock, not only would public officials house displaced families better and save the school year, but they could also pave the way for a long-term recovery of a usable residential stock that should be reintegrated within the city’s housing market, for rental or sale.

A critical impediment to mandating the occupation of vacant buildings for IDPs is the negative legacy of ill-managed squatting during earlier episodes of forced displacement in the country. Many people are understandably wary of considering temporary occupation a viable option. To buttress their concerns, they point to the rich history of trespasses and violent takeovers that often-left legitimate homeowners compromised. They particularly refer to the widespread squatting during and following the Lebanese civil war (1975-1990) when individuals emboldened by the backing of non-state armed groups forcefully occupied apartments across the country. They further argue that rather than reversing neglect and unjust compromises, the post-civil war policies exacerbated the injustice. On the one hand, the recovery of private property was often delayed, prioritizing the well-connected and delaying others. Similarly, post-war compensations to squatters who were being evicted in the 1990s were proportional to the power of the squatters’ political backers rather than the hardship they had endured or their actual housing needs. Following the war, no public incentives or support were introduced for property owners to recover their buildings. Many had left the country, and their properties were abandoned, a constant reminder of the sour experiences of the civil war. In sum, repeatedly poorly managed forced displacements have left citizens understandably wary of options that leverage empty homes as crisis shelters.

Conversely, leaving buildings vacant and people on the street or in schools has encouraged non-state actors to champion illegal occupations, hence reviving the clientelistic practices of the civil war when militias encouraged squatting as a favor to their supporters. The past few weeks have been rife with episodes of forced occupation, some of which ended with the national army pitted against city dwellers, making evictions the single most visible public intervention of an actor mandated to protect the country’s citizens! By shying away from intervening on these properties, state agencies left to local strongmen the task of breaking into buildings and allocating units to citizens they consider their constituencies. The right to housing, a legally recognized entitlement sanctioned through numerous international agreements and pledges signed by successive Lebanese governments is left to informal practices that are far from guaranteeing a just outcome.

For public actors to successfully reclaim abandoned private property as emergency shelters, careful mechanisms should be set in place. A wealth of international experiences can guide this process since the approach has been successfully tried in other national contexts.5 It would be judicious to start with pilot interventions targeting buildings where limited rehabilitation is needed. Budgets can be secured through local and international donors who are currently supporting the management of schools, and some of the repair works can be delegated to willing displaced families. Agreements can be developed with property owners and incentives can be extended by waving overdue property taxes and fees6 or even guaranteeing some level of repairs. Additional protections to property holders can also be secured by drafting contracts with all occupants that guarantee that no compensations will be accrued for their departure and designing an exit strategy within some reasonable timeline aligned with the unfolding violence. An advisory board of legal experts, planners, and social actors can also be set in place to monitor the operations and coordinate building management. Should the crisis extend, the short-term free residency will require some residents to participate in absorbing maintenance and service costs, when and if reasonable.

In closing, let us be clear that we are not calling for the abolishment of the right to private property. Instead, we are arguing that the current crisis makes it even more urgent to balance the unquestioned and unbridled right to private property with the right to housing, which is also inalienable in Lebanon - as is the right to live in dignity, the right to health, and the right to education. It is high time for us as a collective to consider closely why we are ready to sacrifice our children’s learning over the unconditional support to private property even when the latter has been abandoned for over a decade. A bold move by public authorities to mitigate the severity of the crisis on both displaced and host communities is urgently needed. Public actors should leverage their institutional authority and use empty and abandoned buildings. This process should necessarily be brokered and managed by a public institutional guarantor to safeguard a just resettlement of the displaced population and ensure the equitable use of the city’s housing stock.

1 Check platform on “Government Designated Shelters in Lebanon” here.

2 A total of 1172 shelters, mostly public schools have been opened for IDPs, despite some claims about exclusionary practices against non-Lebanese citizens (e.g., migrant workers, Syrian refugees) and single men. Source: Disaster Response Management Unit

3 For more information on the Housing Vacancy in Beirut 2023 study, please check here.

4 Check https://www.lincolninst.edu/publications/policy-focus-reports/empty-house-next-door/

5 Similar mechanisms have proven effective in crisis response elsewhere (Communa in Belgium, Housing for Humanity Ukraine, and elsewhere).

6 A review of property records shows long-overdue legal claims and unsettled built property taxes (municipal and central) on these buildings.