Beirut: A City for Sale?

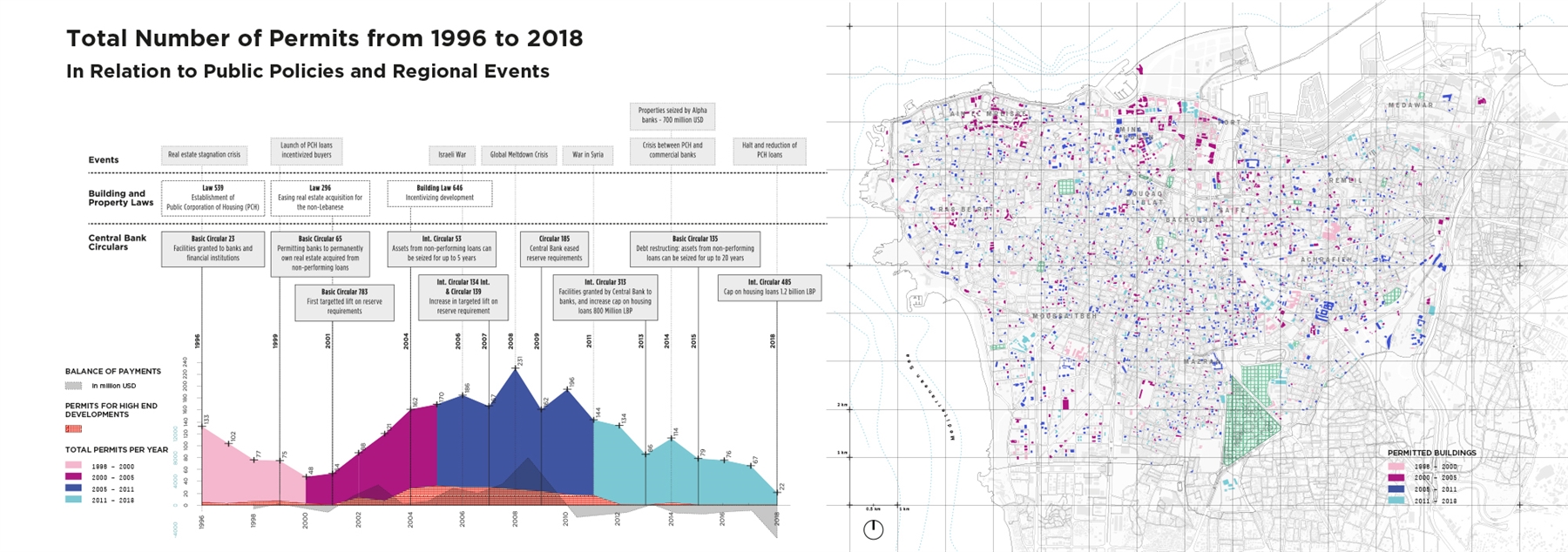

Building Development in Context

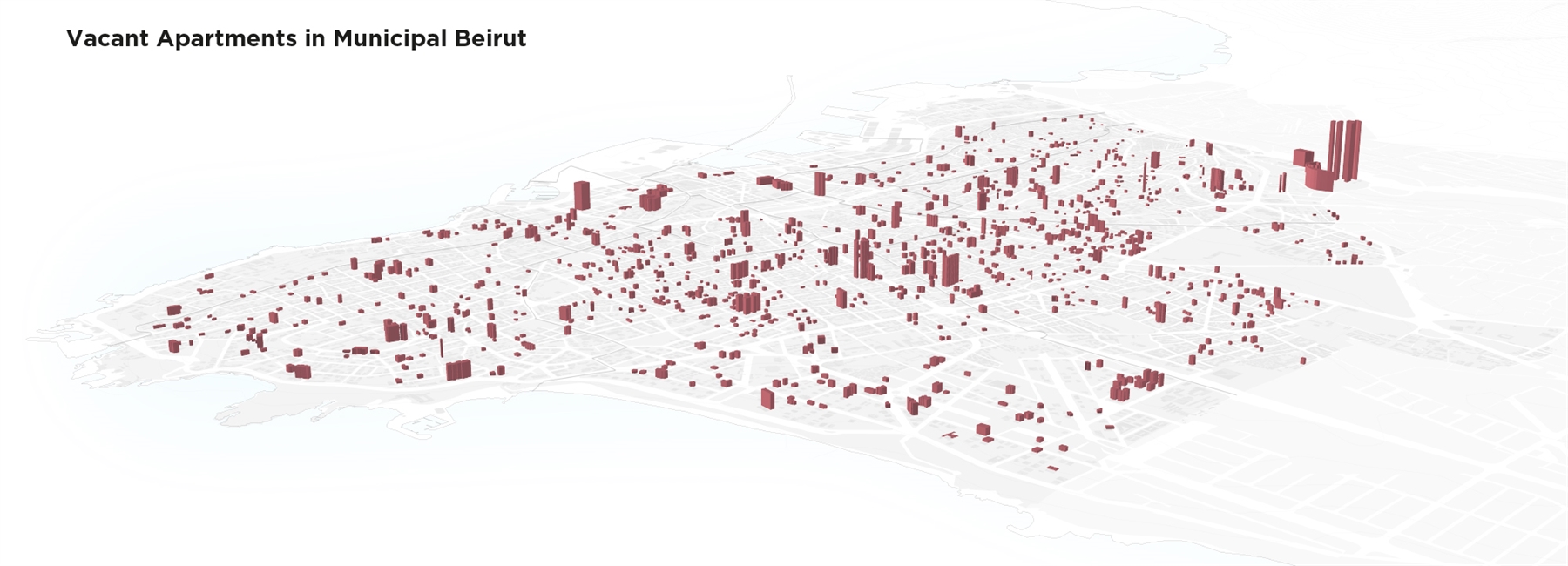

On Vacancy

Vacancy rates are extremely high across the city, particularly among higher end apartments, where rates reach above 50%, but well across the remaining urban districts. By vacancy, we refer to apartments that were found at the time of the survey to be unoccupied and unfurnished. These apartments include apartments still held by developers who await a market recovery before they sell them. They also include apartments purchased as long-term investments, mostly by expatriates but potentially also by rich Lebanese individuals.

Vacancy can primarily be explained by the valuation of land as a reliable investment for the rich local and expatriate elites. The trend is common in countries such as Lebanon where currency devaluation is an endemic risk. This valuation is amplified by a dominant discourse promoted by the powerful real-estate lobby that has institutionalized its influence over the past decade through the establishment of public agencies such as IDAL as well as lobby groups. With strong connections to the political and bankers’ classes, themselves hardly distinguishable from each other, the role of the real-estate lobby has been heavily publicized in the local press through advertisements, conferences, events, and other occasions where a perception of reliability and success is promoted for the sector.

Vacancy is facilitated by the tax structure which exempts empty apartments from municipal and property taxes. Conversely, conceptualizing land as an asset comes at a hefty price for the vast majority of Lebanese households who suffer from the heavy burden of shelter costs on their general expenditure. It is indeed ironic that while thousands of Lebanese households struggle with long daily commutes and many young couples choose to emigrate and/or delay life plans because of the unaffordable housing prices, one in four apartments is vacant in the city.

Beirut's Developers

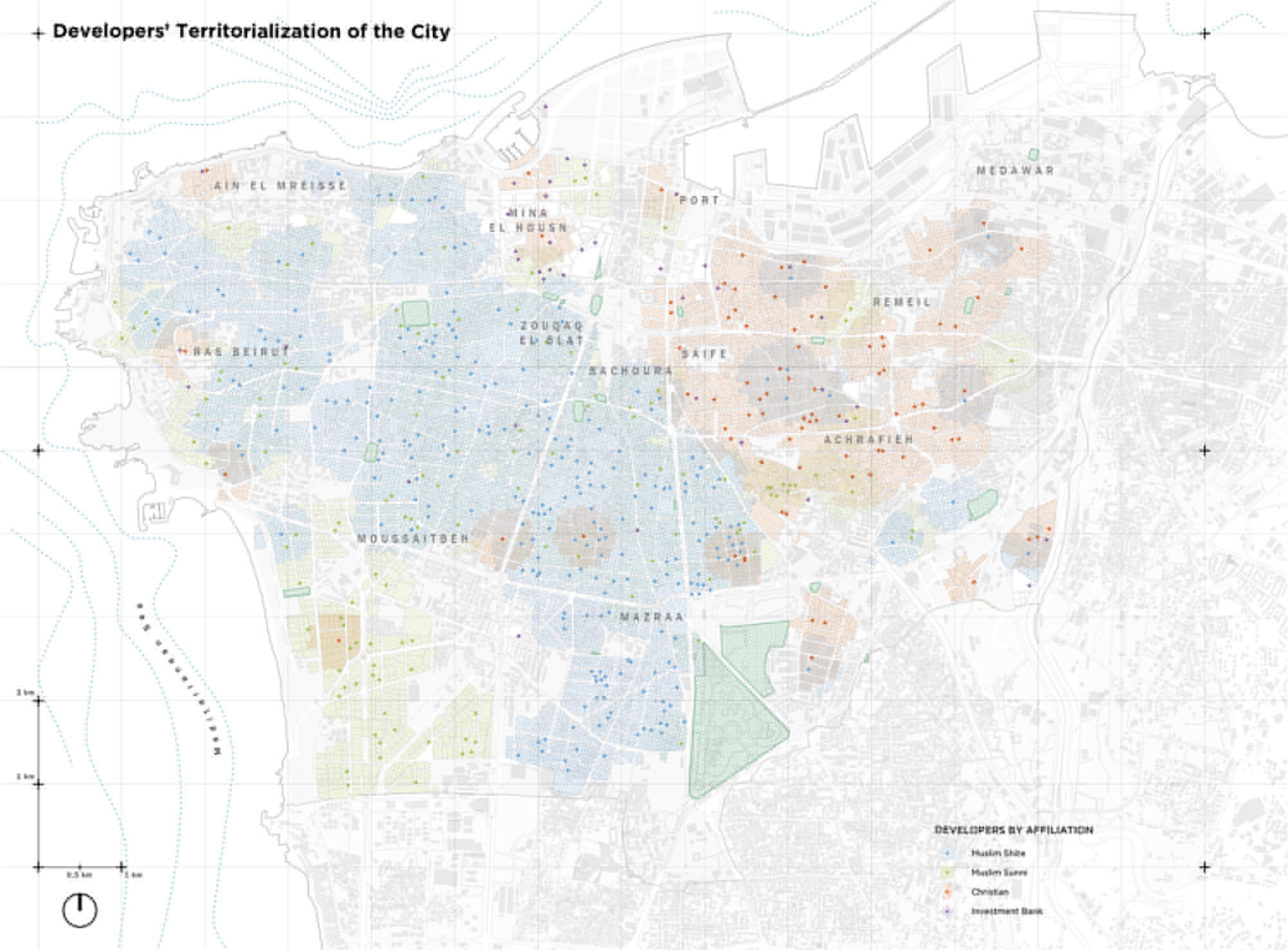

To understand how the territorial organization of space is produced, one needs to account for the deep embeddedness of development practices within the socio-political organization of society and its multiple levels of governance. The study points to the role of families, political parties, and religious institutions in channeling economic transactions and formal permitting processes. It reflects the importance of social and symbolic capital for specific actors to impose themselves as long-term developers, capital cultivated and accumulated among a relatively restricted number of actors who can be considered successful established developers. In addition, building activities are spatially organized through the logics of class

and sectarian segregation that dominate everyday interaction in Lebanon.

Religious/Sectarian enclaving continues to dominate the urban

geography, where a developer’s sectarian affiliation is highly

correlated with the distribution of his activities. Thus one clearly

reads the marks of the civil war territorial divisions but also the

subsequent political/sectarian tensions through the distribution of

building activities. On the other side, a financial elite composed of development agencies affiliated directly or indirectly to banks, investment companies, and well-off investors operates within a territory defined along class lines and controls primarily the sea-view and some of the elegant districts of Achrafieh.